The Irish History Problem

Why research in Ireland is so difficult, depressing and often wrong…

“Ireland may be regarded as the first English colony...”

As Professor Jane Ohlmeyer has observed Ireland functioned as a testing ground for the British Empire, where imperial and anglicising policies, race-based ideologies, and “tools of empire” like mapping were developed, all underpinned by sectarianism, cultural stereotyping, dehumanisation, and land expropriation.

Despite being victims of English imperialism, the Irish also actively participated in the empire, serving in its armies and administrations, as the United Kingdom created the largest empire the world has ever seen.

I would argue, all this was not just colonial appropriation of a country, but also involved the more insidious and durable colonialism implanted in the minds of those who lived here…

Loss of records

So what has Colonial and Post-Colonial perspectives to do with your Irish history research? Researching Irish history presents several specific challenges. Overcoming these challenges requires careful methodology, sensitivity to biases, and often interdisciplinary collaboration.

Many sources are from a British perspective, introducing potential biases, especially from an official point of view. Native oral traditions and Irish language sources were almost completely ignored by authorities.

The destruction of native cultural institutions, and forcing the Catholic church ‘underground’, led to fragmentary and scattered records for the few that survived.

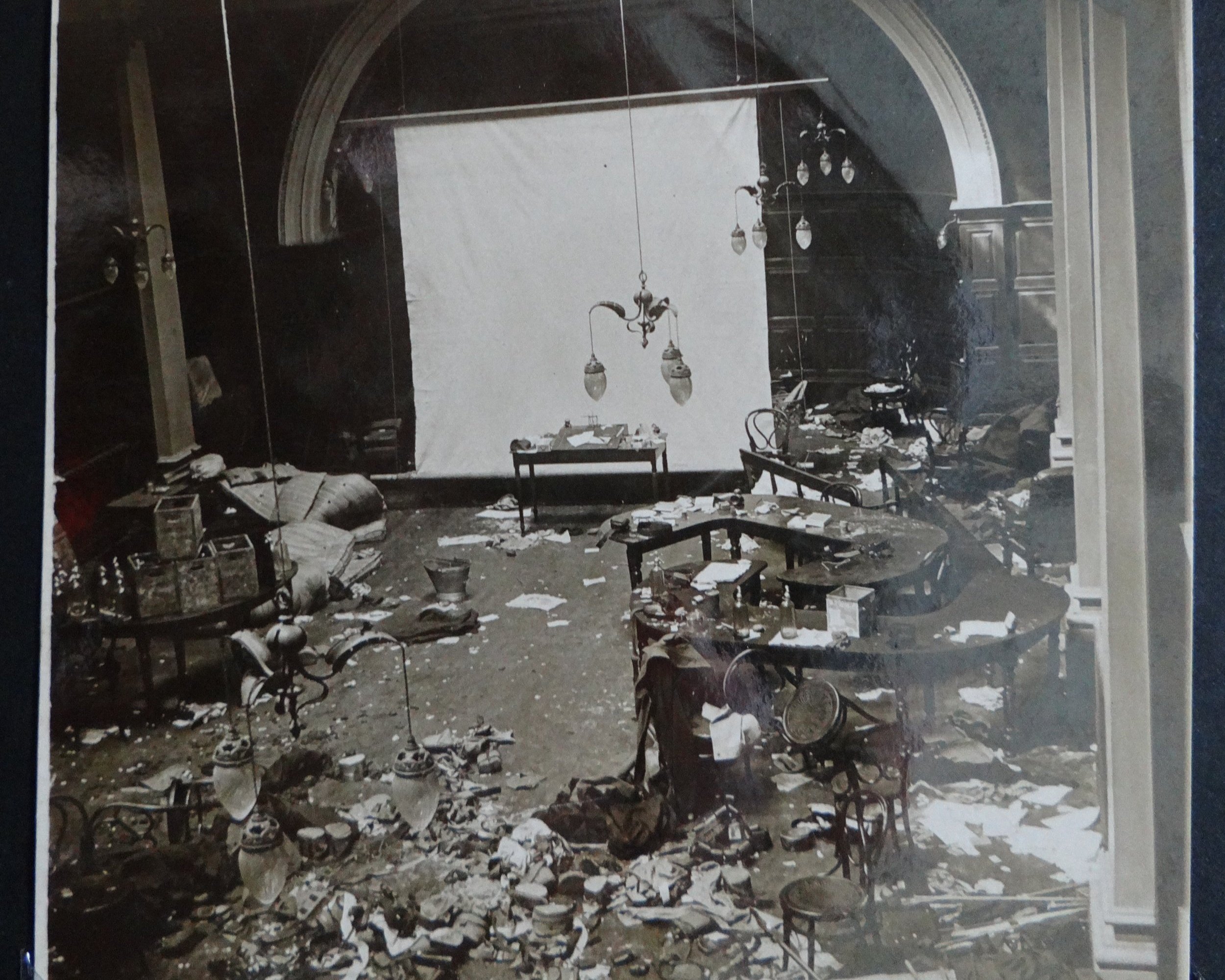

Significant official documents were destroyed, during rebellions against the British state, while most notably the destruction of the Irish Public Record Office occurred during the Irish Civil War.

Post-Colonial history has mainly been interpreted through a lens of nationalism, or armed resistance against the state, even adopting the old value system of the British establishment for evaluating Irish history. This led to minorities and lower classes often underrepresented in historical accounts.

Sensitivities surrounding the Northern Ireland conflict (1960s - 1998) led to the tempering of Irish history research and alleged politicisation of relevant academy study.

The post-Great Famine haemorrhaging of local communities through emigration led to the loss of sustainable reservoirs of local knowledge and the dispersal of family history through the global Irish diaspora .

The Irish State and its local authorities have failed to create a spirit of archive conservation within its institutions, much less adequately provide for the protection of Irish heritage sites, landscapes and documentary records.

“The gorse was in bloom, the fuchsia hedges were already budding; wild green hills, mounds of peat; yes, Ireland is green, very green, but its green is not only the green of meadows, it is the green of moss - certainly here, beyond Roscommon, toward County Mayo - and Moss is the plant of resignation, of forsakenenness. The country is forsaken, it is being slowly but steadily depopulated...”

The impoverished counties at the extreme west of the country, fared the worst for surviving historical records, while its loss of population has continued to the present day, with entire communities falling forever silent.

Germany’s greatest writer and Nobel laureate, Heinrich Böll, could feel the lonely sorrow of the west of Ireland permeate his being as he ventured here in the middle of the last century. Today, remnants of the stories of the ‘old people’ linger in the shadows of ruined history, where ancient landscapes still whisper the names of those generations who had to journey across the ocean and ‘go into the West’, denuding the land of its people and their stories.

Some remained… and have kept their communities alive, breathing life into the records of the past, so that the old stories may yet be read aloud to long-lost sons and daughters returning from over sea and lands via an invisible thread still linking a land to its people.

Visit our two collections of history records using the buttons below.

Dr Liam Alex Heffron, M.A., Ph.D.

As a native of the west of Ireland, I have grown up immersed in the distinctive cultural heritage that sets this region apart. From a child, I have been curious about the stories told by ‘the old people’ and been captivated by a wild landscape whose ‘lumps and bumps’ bear silent witness to thousands of years of human activity. I have always wanted to know more of what has happened here…

After much life experience, I am now using my training, experience and expertise as a historian and actor, to discover, interpret and and tell these lost or hidden stories.

So please join me on our quest to dig up new records never before publicly seen, or reinterpret existing works in radically different understandings…